Converting Word-Babble Into Sentences.

Writing concise and clear programs is beneficial for business. It avoids unnecessary complications and allows for easier future modifications.

I had trouble finding a program that only breaks sentences in automatically generated captions. The programs I found tried to do more (e.g. all punctuation), were difficult to install, complicated to understand, and had higher error rates.

This is all too common in deep learning programs and almost all useful NLP uses deep learning.

I wrote my own solution, which is about 120 lines of code. It predicts well enough for what I need. I hope it inspires your NLP code to look similar.

Why this task? Sentence restoration is important in NLP because most libraries and programs assume that text input data consists of sentences. That is true with written texts but not spoken text and the mouth is more prolific than the pen.

We have software that can convert speech to text, like automatically generated captions. However, there are some challenges with this process, especially when it comes to punctuation and capitalization. YouTube, for example, does not always provide accurate punctuation in its captions. Additionally, speakers often use partial sentences, which can make the transcription less straightforward.

The code in this GitHub repository creates a deep learning model that can accurately (F1>.97) identify sentences in speech transcripts. The code also includes some unique techniques for solving sequence-to-sequence problems.

This block of code follows a coding style influenced by Ward Cunningham, the inventor of eXtreme Programming (the original and most agile programming method). Ward’s mantra is “Do the simplest thing that could possibly work and then iterate.” The code doesn’t use classes because the focus is on functionality rather than reusability. Data science models, especially those related to natural language processing (NLP), are often too rapidly obsoleted to justify reuse.

In programming, it’s important to use clear and meaningful variable names. However, often in machine learning, one-letter variable names are used (trying to look like mathematical formulas.) But a really good math formula is meant to be pondered for hours meaning you easily recognize what a one-letter name means.

Code is almost never a really good math formula. There are hundreds or thousands of lines of code, and it’s tough to remember what they all mean. This is where bugs are born. If your code is getting too long, break a line up onto several lines to make it easier to read.

So how well does my program work? (because stats like F1>.97 do not impress end users). Here is an example from the opening of this video.

Yikes! Auto-generated closed captions only display a handful of words at a time, making sentence breaks somewhat obvious. However, when it comes to NLP (Natural Language Processing) tasks, like using BERT models, the lack of sentences is a non-starter.

Now here’s how the model I built performed on that text:

Hey folks. Dr mike ezratal here for renaissance periodization nucleus overload training. You’ve been asking about it. And i’m answering. We’re going to take a critical look upsides. Downsides so on and so forth. Now before we start different folks have different ideas slightly of what this means. We’re sort of shooting for the average. So i’m really sorry. If i mischaracterize it. I promise it wasn’t on purpose. I did some interneting to try to find out what it is. That it really was. I found out some stuff. Hopefully. I’m not too far off the mark. So today we’re going to talk about what nucleus overload training is. What are the potential benefits to it. What are some unanswered questions about it. And what are the potential. Uh. Upsides. Or sorry. Potential downsides. Or those benefits unanswered. Questions downsides. And then lastly should you try it because you’re probably thinking should i try. Let’s get started. So first of all what is nucleus overload training. It’s essentially. And there’s a lot of ways to skin the cat. The cat hates all those ways. By the way it’s miserable. Um. It’s training with a lot of volume and intensity what you can term an unsustainable amount of volume and intensity in the long term. Okay. And this is usually done for a period of several weeks to a month and potentially more will be charitable and say two to four weeks. But some of the programs call for six weeks. Plus. That’s a whole level of insanity. That’s a bit different. But it’s really just a ton of psychotic training. Which may be a good thing.

Not perfect, but it can be challenging even for a language expert to translate Mike’s informal speech into grammatically correct English. However, this type of speech is common in everyday conversations.

Keeping in mind “the simplest thing that can possibly work” I do not worry about punctuation or sentence types, I just need to separate the text into sentences for further processing by BERT.

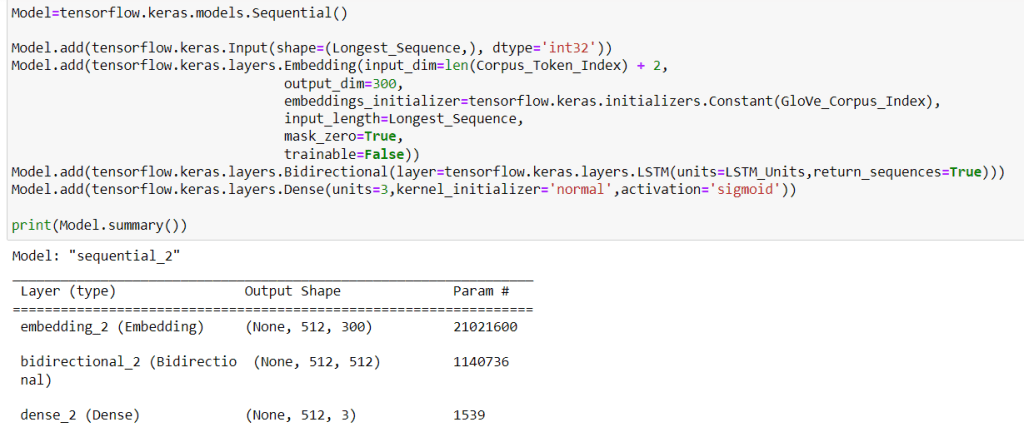

How did I solve this? To solve the task of classifying words as sentence-ending or not, we can use a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). The RNN helps consider the word order in the classification. Instead of using a complex encoder-decoder model, we can simplify the approach to focus on the binary classification of each word. However, there are still some challenges to overcome, such as handling padding, managing long texts, dealing with imbalanced classes, and selecting the appropriate tokenizer.

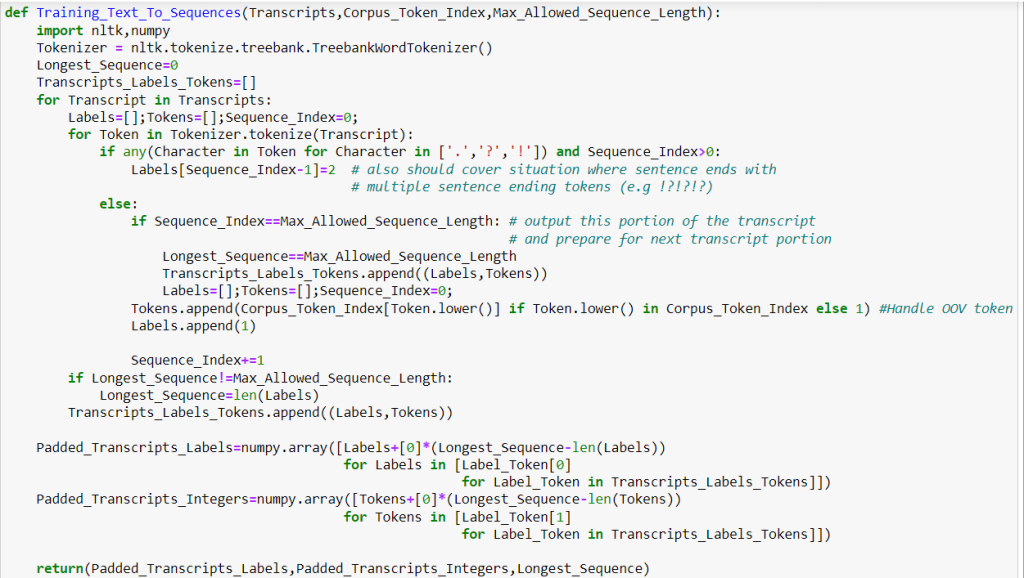

A tokenizer is a tool that separates a group of words into individual words or parts. Different tokenizers do this in different ways. When using a pre-trained word model like the pre-trained GloVe model that uses 4 billion tokens from the common crawl, it’s important to know what tokenizer was used to create it. The standard Keras tokenizer, for example, does not split up common contractions like “I’m”, “we’re”, “don’t”, etc. So those words are ignored by GloVe. The pre-trained GloVe word embeddings were created using the Stanford Parser, which is mostly based on the Penn Treebank tokenizer which is in NLTK among other sources.

I compared the performance of the Stanford and U of Penn programs. Both programs created very similar tokens, but the Penn code in Python ran faster in my experience. The Stanford code, on the other hand, is in Java and requires a Java installation. Therefore, I chose the Penn code from NLTK.

In natural language processing, word tokenizers and GloVe are used to convert words into numbers. This is necessary for mathematical and statistical operations, like machine learning. In the past, word frequencies like TF-IDF were used to represent words numerically. But about ten years ago, Google and Stanford introduced Word2Vec and GloVe, which calculate word co-occurrences to create more detailed (i.e. a multi-dimensional vector for each word or subword) and meaningful numerical representations of words. These methods provide a richer semantic value for each word.

In simple terms, BERT and similar transformers recognize that words can have multiple meanings. They consider how words co-occur in different situations. But it requires sentences. So for this sentence-forming task, GloVe, a single definition per word vector system, is used.

In most cases, modern NLP uses deep learning techniques. These techniques involve several steps in a supervised learning classification model:

- Input text converted to integers

- Lookup integers in a word embedding table (in this example GloVe) and convert them to floating point numbers/vectors

- Send these numbers as inputs into one or more layers of a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) or RNN (in this task I used an RNN because sequence information is important)

- Send the output of step 3 to one or more dense layers with the final one classifying the result into the most likely class number.

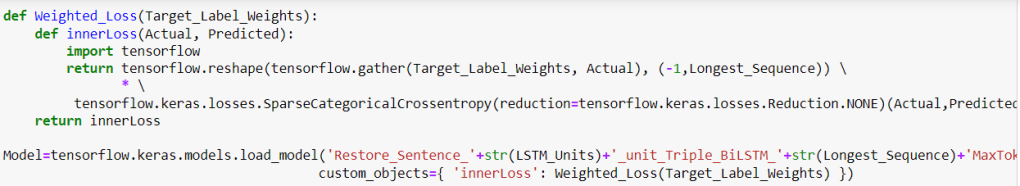

For the RNN I used bidirectional Long Short Term Memory (BiLSTM) layers because where a sentence ends within a string of words is dependent on the words before and after the sentence ends. LSTMs learn the relevance of the distance from the end of the sentences in the sequence of words.

In the first block of code, some global variables are set. These variables were modified multiple times during testing to determine the most effective option. The comments in the second block of code are self-explanatory.

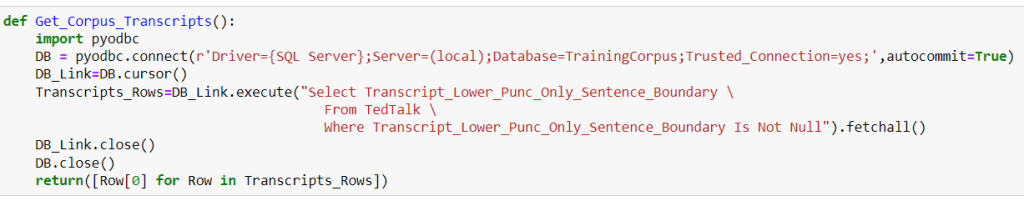

The third block collects the data that I will use for training. Instead of using the pandas library, I prefer using the pyodbc to interact with SQL databases. By using simple Python code and good variable names, I can avoid the more complex, non-SQL-like inconsistent API of pandas.

I used transcripts from 4000 Ted Talks for training data. The speakers in these talks practice their speeches and have good grammar. Although YouTube speakers often ramble nongrammatically, the Ted Talk transcripts are still useful for my purposes.

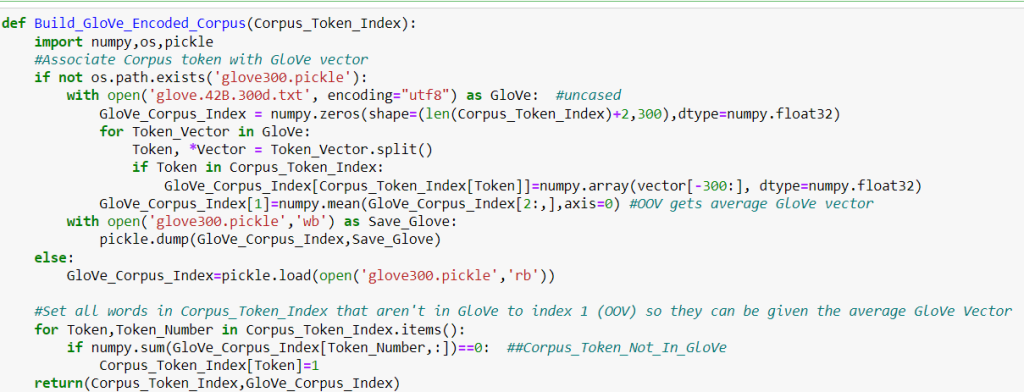

This next code creates two dictionaries. One dictionary assigns a unique integer to each word or token, and the other dictionary assigns a vector of decimal numbers (using GloVe) to represent the word/token in a pre-trained model. If a word is not found, it is given a special code (OOV or Out Of Vocabulary). The dictionary also includes a symbol for padding.

Padding is required to ensure consistent input length for the RNN. Keras’ padding function is more complex with apparent side effects. So I used this simple padding logic:Tokens+[0]*(Longest_Sequence - len(Tokens))

The code to turn any text into integers compatible with these two dictionaries follows:

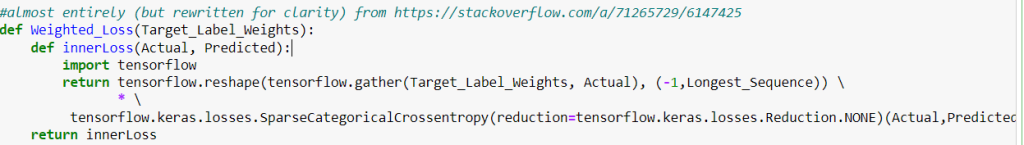

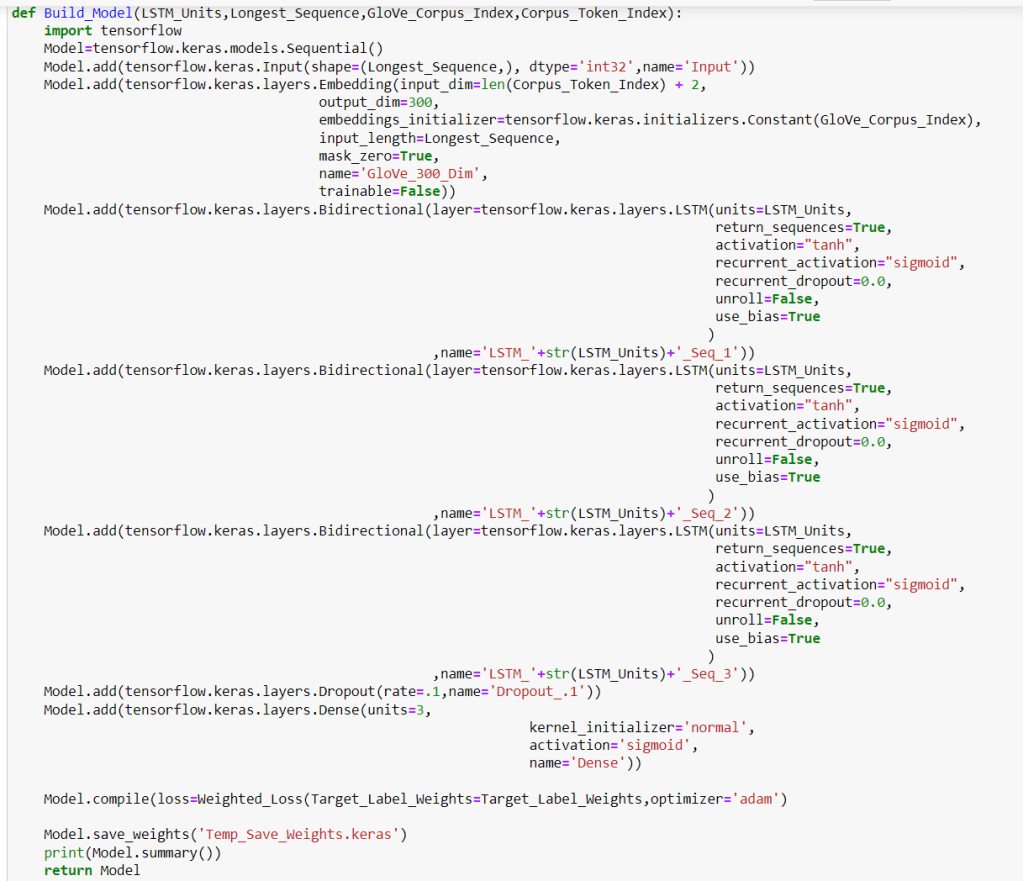

In order to weight the cost of wrong predictions for each token in a sequence, you’ll need to use a custom loss function. This differs from the typical method of weighting prediction costs for a single text output. The following code is necessary for handling this situation:

This loss function is referenced when you compile the model.

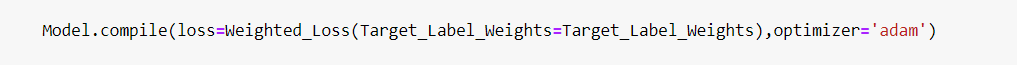

When you use this model to make predictions, you need to have the function mentioned earlier in the program. Additionally, the model must be loaded into memory, usually by restoring it from a saved version on disk. Here’s an example of code for a prediction program:

For the sentence restoration task, I used a somewhat more elaborate and accurate model than the simple one described above.

When training deep learning models, it’s recommended to use k-fold cross-validation and early stopping. K-fold cross-validation estimates out-of-sample error, and early stopping reduces overfitting. For practical purposes, 10 cross-validation iterations is a good value of k, but a lower number may produce sufficiently consistent error levels for your training time needs. Early stopping stops training when the validation loss stops decreasing, preventing the model from memorizing the training data instead of better predicting unseen inputs. Finally, you can use the average number of epochs from cross-validation as the number of epochs for the final training.

Cross-validation and early stopping are shown in the upper part of the following function:

The code includes a helpful function called ModelCheckpoint that can be used to save your progress during training and resume from the last saved point if needed. In the provided cross-validation loop, the function Model.fit() is called multiple times. To prevent overfitting and data snooping, it’s important to reset the model weights before each iteration of Model.fit().

The F1 score is a useful metric when dealing with unbalanced data. It takes into account the predictions for both positive and negative classes. Additionally, because the input data is padded to have a uniform length for RNNs, the code explicitly ignores the predictions for padded elements.

Finally, after doing the k-fold cross-validation retrain the model with the full data set.